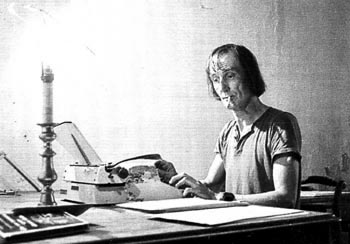

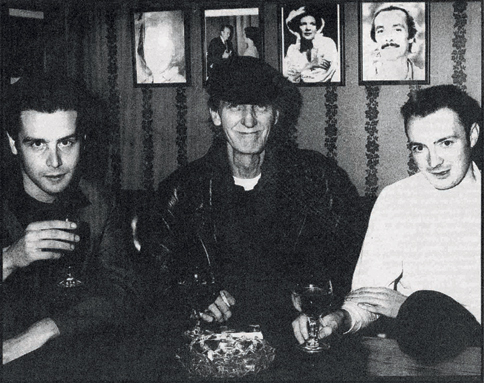

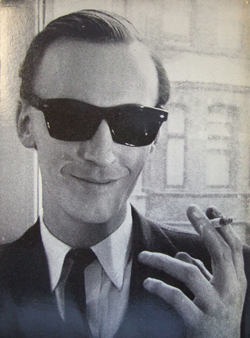

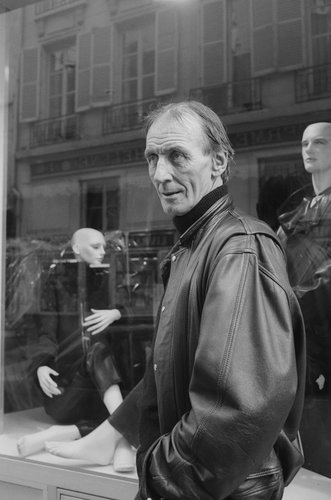

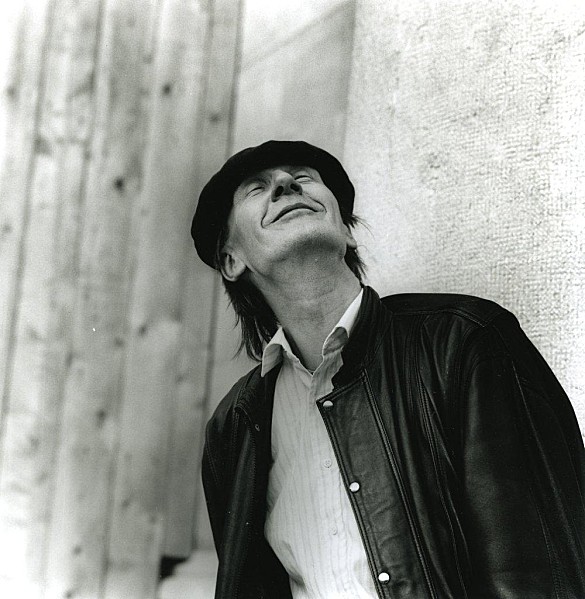

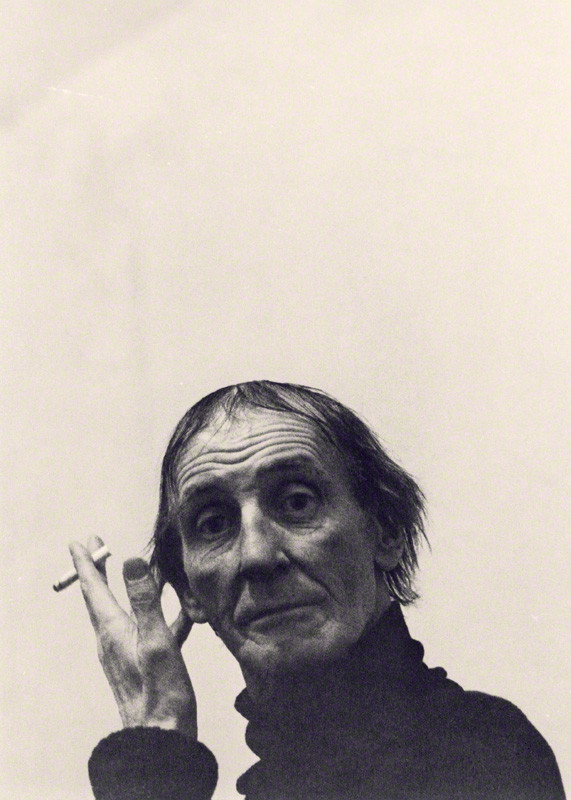

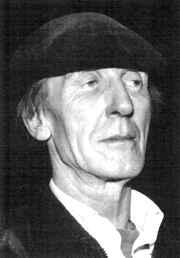

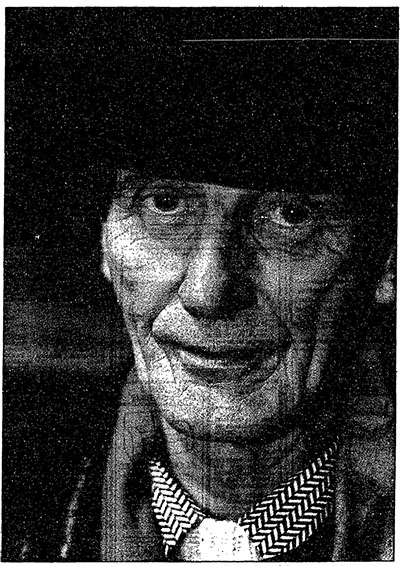

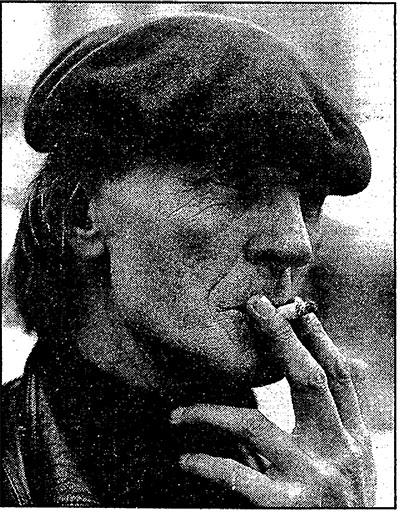

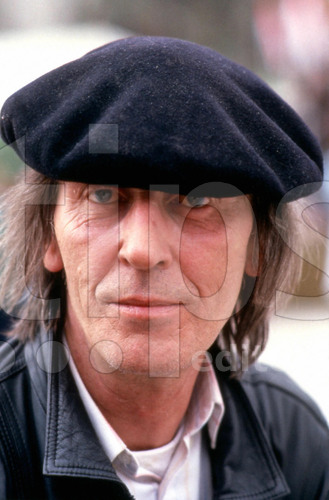

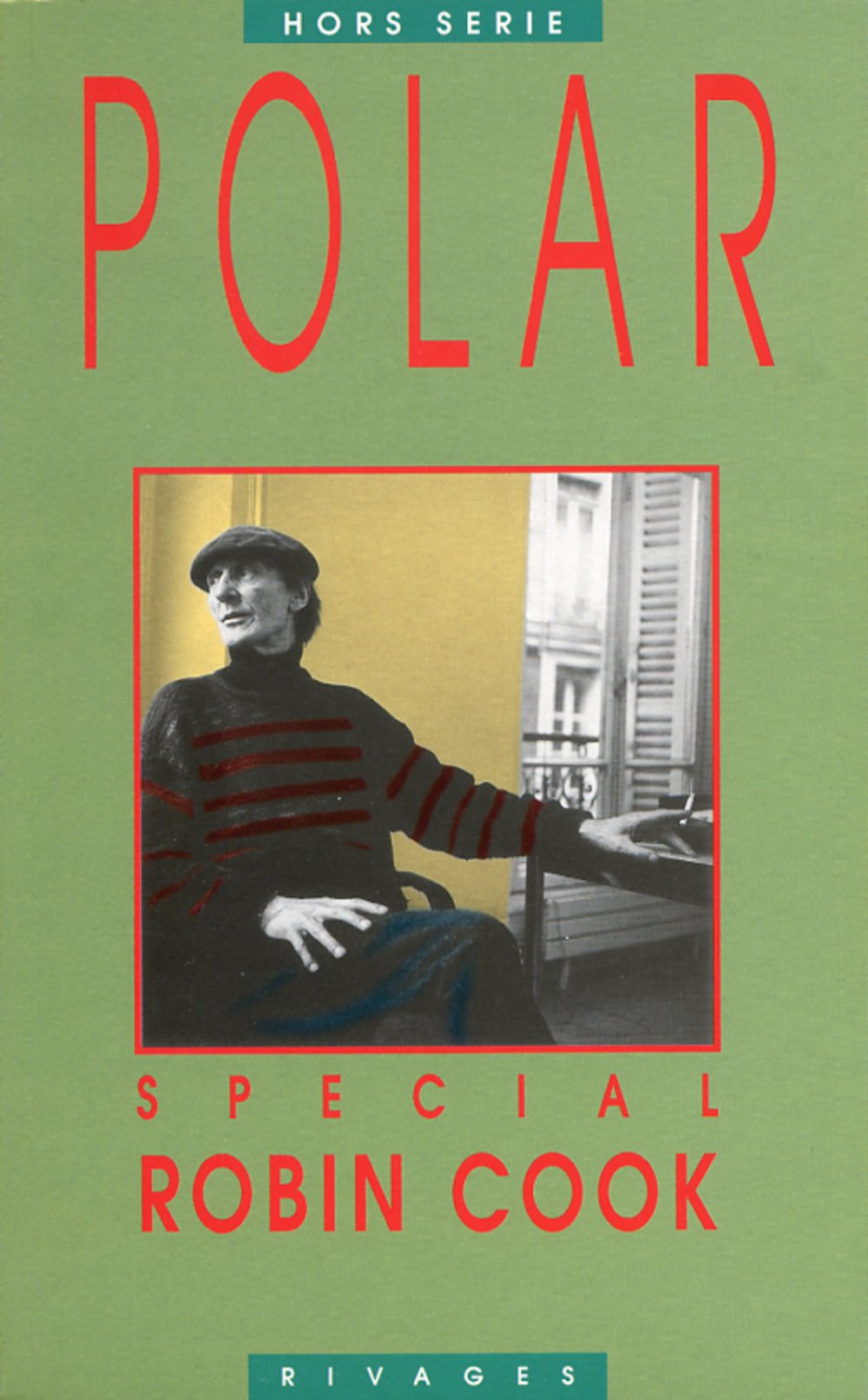

of Mr. Derek Raymond, alias Mr. Robin Cook, the Author.

(hosted on a questionable url)

ugly since 2005

last updated: 18 September 2014

Derek Raymond

1931-1994

Pseudonym of Robert William Arthur Cook. He was born in London. He also wrote under the pseudonym 'Robin Cook'.

The son of a textile magnate, he dropped out of Eton aged sixteen and spent much of his early career among criminals and was employed at various times as a pornographer, organiser of illegal gambling, money launderer, pig-slaughterer and mini-cab driver.

Titles and year of publication (*)

As 'Robin Cook':

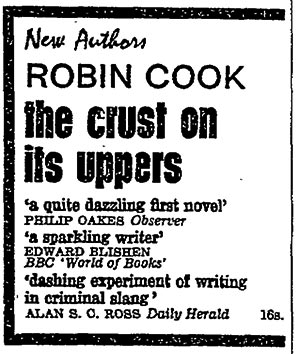

1) The Crust on its Uppers 1962

Amazon Amazon UK

Review by Bernard Share (26 May 62)

Review in Publisher's Weekly (28 June 93)

Spotlight by Dennis Cooper (27 November 09)

2) Bombe Surprise 1963

Review in The Times of India (8 December 63)

Commentaire par L'Oncle Paul (03 Août 13)

3) The Legacy of the Stiff Upper Lip, or, The Astonishing Social Hinterland of a Lapse 1966

Review by Mary Holland (03 July 66)

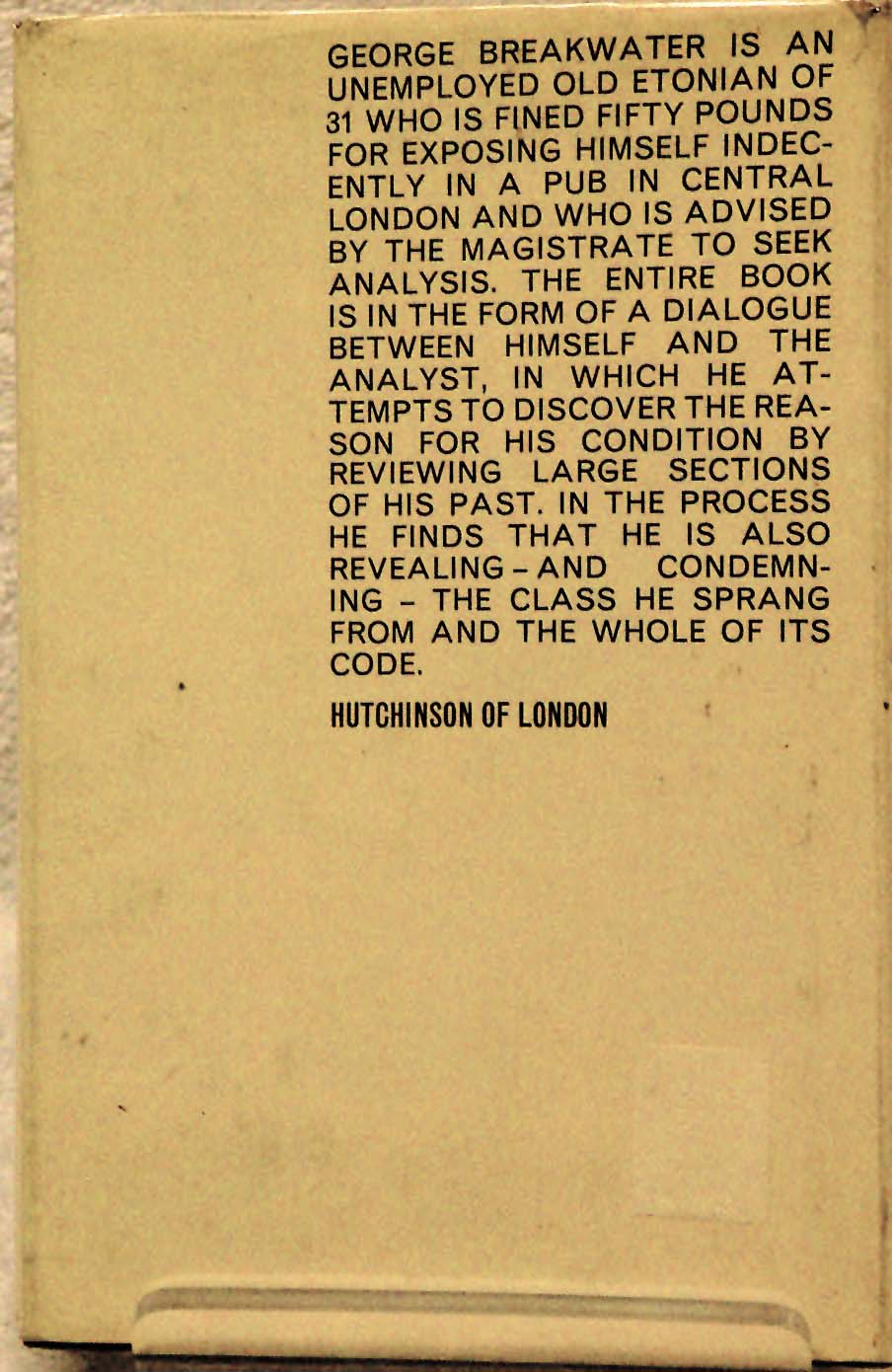

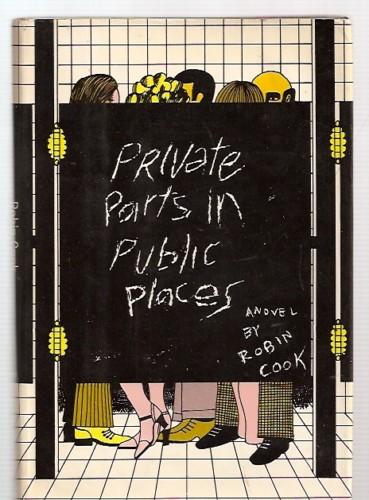

4) Public Parts & Private Places 1967 (**)

Review by Christopher Lehmann-Haupt (26 March 69)

Review by Richard Boston (30 March 69)

Review by Geoffrey Wolff (08 June 69)

Commentaire par L'Oncle Paul (05 Août 13)

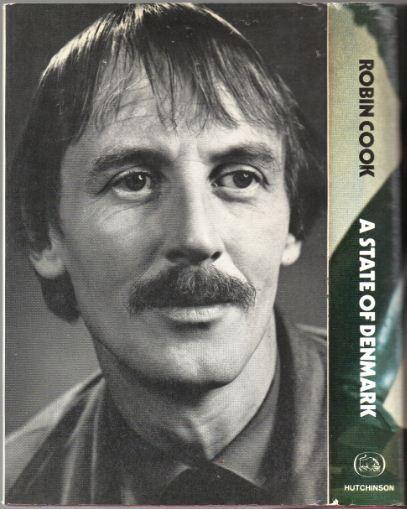

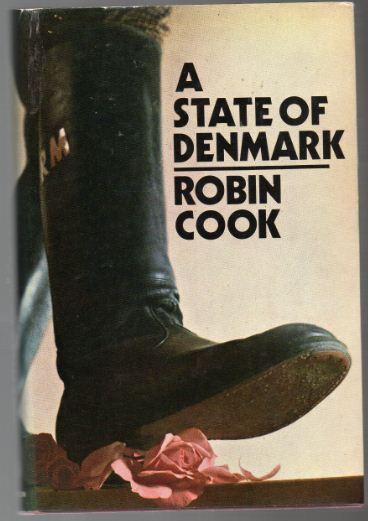

5) A State of Denmark 1970

Amazon Amazon UK

Review by Bruce Williamson (15 August 70)

Review by Stewart Home! (18 February 07)

Review by Cathi Unsworth (August 08)

Review by Sam Urquhart (10 August 09)

Review by David Roodyn (12 August 11)

6) The Tenants of Dirt Street 1971

Review by Stephen Wall (14 November 71)

Review by Bruce Williamson (27 November 71)

Review by Virginia Osborne (20 May 72)

Critique par Eireann Yvon (?? ∞ ??)

As 'Derek Raymond':

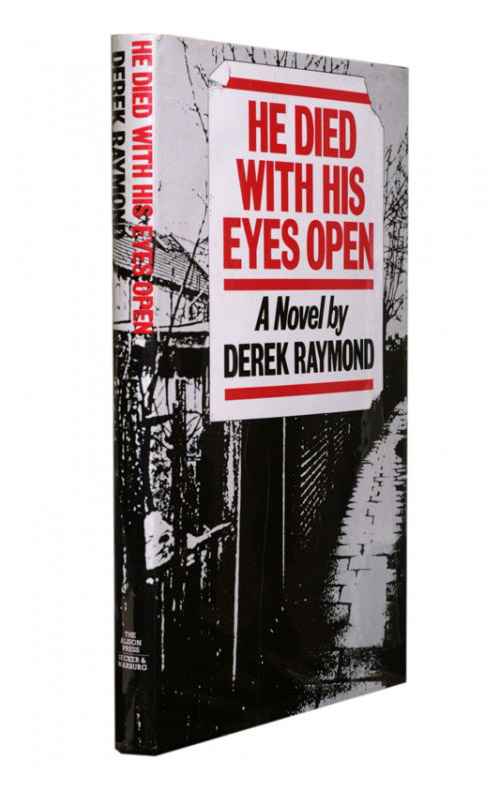

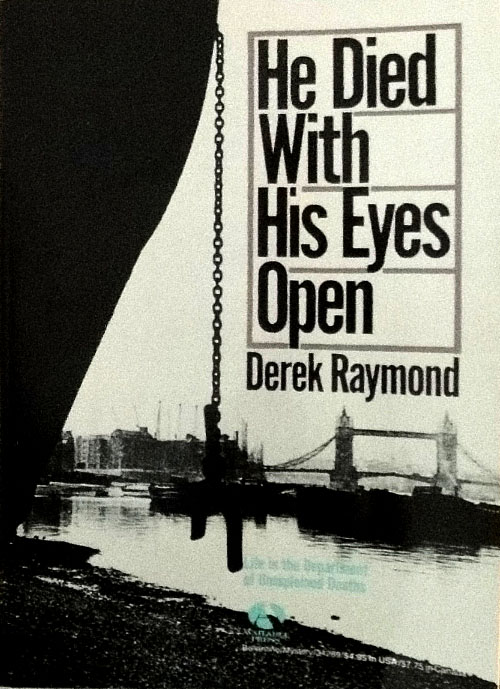

1) He Died with His Eyes Open 1984

Amazon Amazon UK

Review by Colin Ricketts (29 July 07)

Review by Jonathan McCalmont (04 March 09)

Review on His Futile Preoccupations (06 June 09)

Review by Brian A. Oard (06 June 09)

Review by J. Kingston Pierce (04 December 09)

Review by Rob Kitchin (18 March 11)

Review by P.J. Coldren (November 11)

Review by A.J. Kirby (04 October 11)

Review by Joe Hartlaub (01 December 11)

Review by blahblahblah Tony (16 July 12)

Review by Marie (13 August 12)

Review by A.L. Kennedy (10 March 13)

Review by Gabrielle Gantz (10 March 13)

Review by Keishon (04 April 13)

Review by Nico Vreeland (12 April 13)

Review on brothersjudd.com (07 July 13)

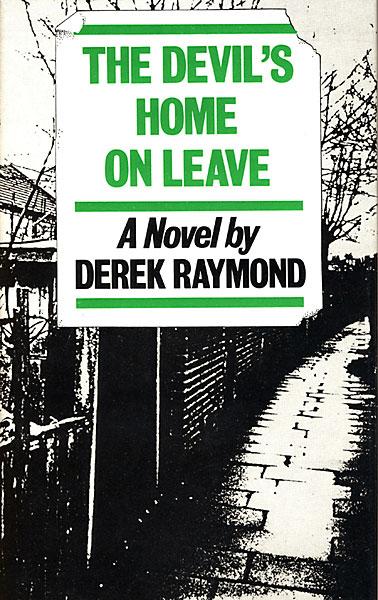

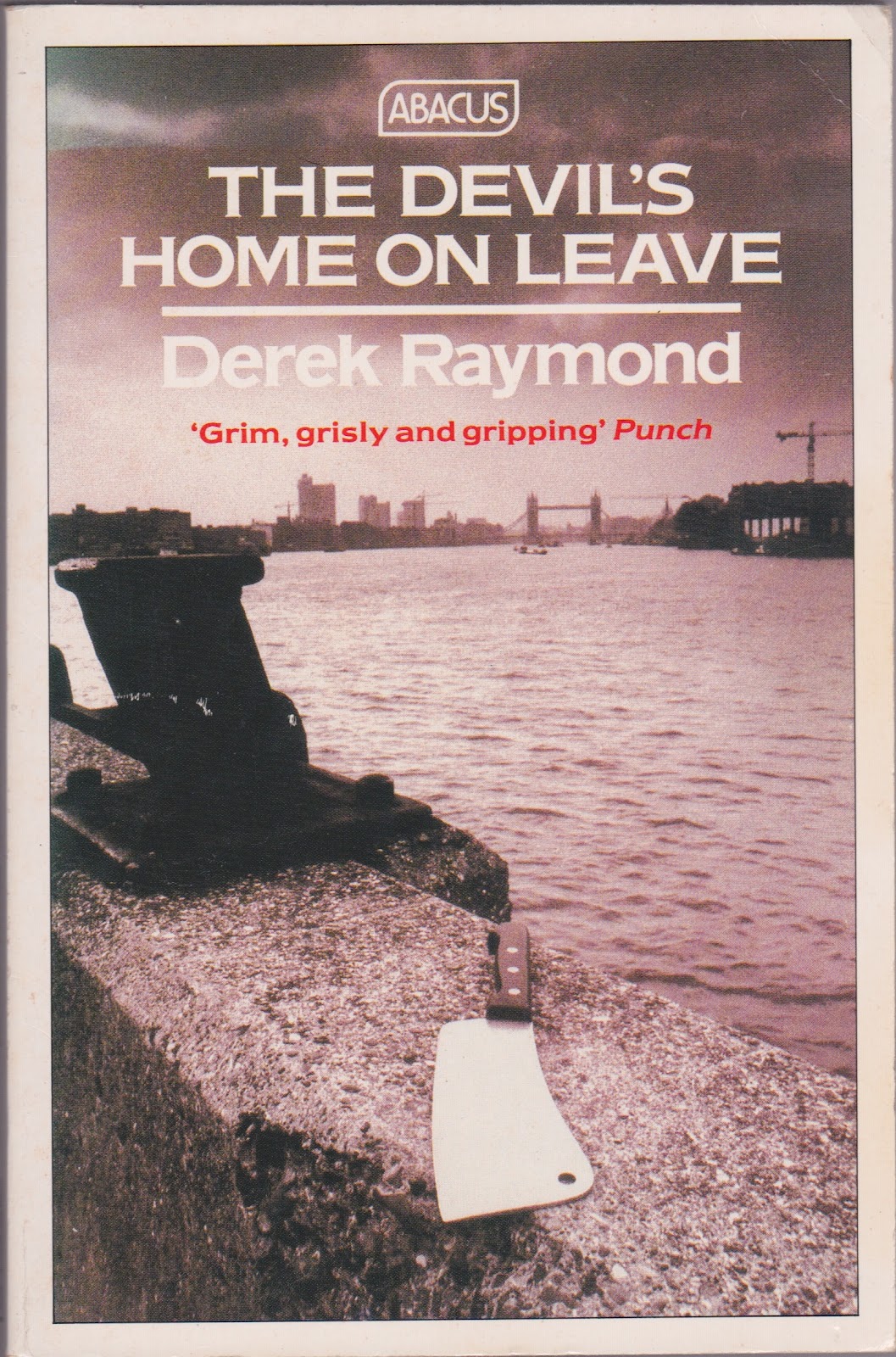

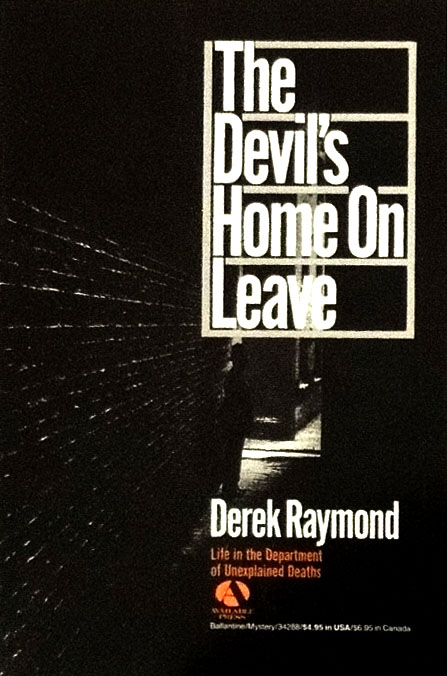

2) The Devil's Home on Leave 1985

Amazon Amazon UK

Review by Heloise Merlin (08 October 09)

Review by J. Kingston Pierce (11 December 09)

Review by Keishon (09 April 13)

3) How the Dead Live 1986

Amazon Amazon UK

Critique par Eireann Yvon (?? ∞ ??)

Review in Kirkus (01 March 08)

Starred Review in Publisher's Weekly (03 October 08)

Review by Will Self (13 Sept 07)

Review by Nathan Cain (17 March 08)

Review by Max Cairnduff (27 July 09)

Review by J. Kingston Pierce (18 December 09)

4) I Was Dora Suarez 1990

Amazon Amazon UK

Review by Jonathan Woods (12 June 2008)

Review by Bruce Grossman (25 September 08)

Review by Ali Karim (18 December 08)

Review by J. Kingston Pierce (08 January 10)

Review by Robert Carraher (12 December 11)

Review by Ignacio Brown (02 December 10)

Review by Barry Graham (18 February 12)

Review by Max Cairnduff (10 February 12)

Review by Keishon (19 April 13)

Review by Charles Beckett (10 September 13)

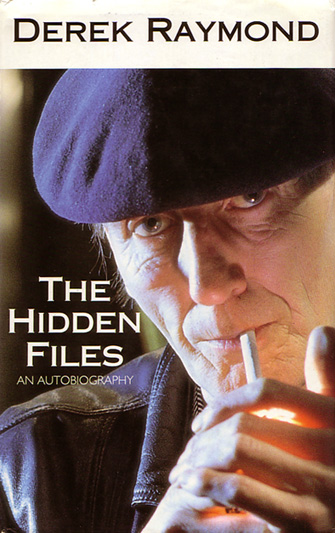

5) The Hidden Files 1992

Review by D J Taylor (31 August 92)

6) Dead Man Upright 1993

Amazon Amazon UK

Review by Helen Birch (22 January 94)

Review by Jeff VanderMeer (17 May 09)

Review by J. Kingston Pierce (15 January 10)

Review by Martin Stanley (23 September 11)

Review in Publisher's Weekly (07 May 12)

Review by Nick Pinkerton (09 May 12)

7) Not Till the Red Fog Rises 1994

Review by Jane McCloughlin (08 January 95)

Novels Published in French:

1) Le Soleil Qui S'Eteint (translation: "The Sun Extinguished Itself" / original english title: Sick Transit) 1983

Critique par Jean Dewilde (28 Septembre 12)

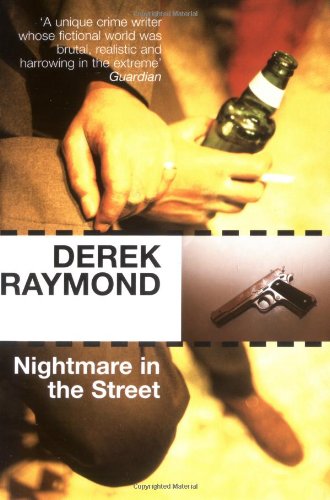

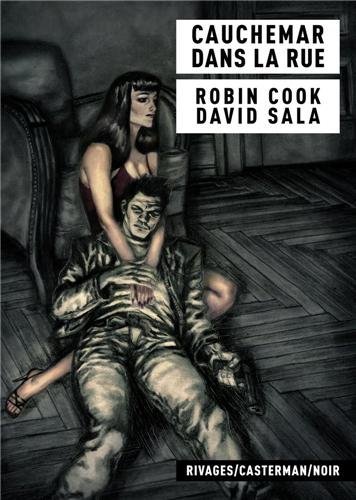

2) Cauchemar Dans La Rue 1988

Published, in English, as Nightmare in the Street 2006

Amazon Amazon UK

Critique par Eireann Yvon (?? ∞ ??)

Review Nicholas Royle (04 Oct 06)

Review by Chris Petit!! (10 Oct 06)

Review in Kirkus (15 Oct 06)

Review by Spadge Dooley (26 July 07)

Review by Nicholas Royle (04 Oct 06)

Review by Mike Cane (06 June 07)

Recensione di Andrea Consonni (29 November 10)

Adapted, in French, as a graphic novel by David Sala in 2013

Amazon FR Amazon CA

Entretien avec David Sala (2013)

* Bibliographic Information kindly provided by Iain Sinclair

** Published in America (1969) under the less clever title of Private Parts in Public Places

Anthology Appearances:

1) "Every Day Is a Day In August" in New Crimes, ed. Maxim Jakubowski, London: Robinson, 1989.

2) "Changeless Susan" in Constable New Crimes 1, ed. Maxim Jakubowski, London: Constable, 1992

3) "Brand New Dead" in London Noir, ed. Maxim Jakubowski, Serpent's Tail, 1994

Note: an excerpt from Not Till the Red Fog Rises

4) "Changeless Susan" in More Murders for the Fireside, ed. Maxim Jakubowski, Pan, 1994

5) "Nightmare in the Street" in Fresh Blood, ed. Mike Ripley & Maxim Jakubowski, London: Do-Not Press, 1996

Note: the first chapter of Cauchemar Dans La Rue

Back to top

(Many thanks to the indefatigable Mike Cane for help with finding these photos and other such materials.)

Back to top

many covers can be clicked for larger sized images

never shall our hearts forget this sight:

2011: Melville House publishes The Factory Series in new, orange editions

Back to top

Back to top

The Visionary Detective by Joyce Carol Oates (!) in the New York Review of Books. Dated: 20 June 2013

Doors Closing Slowly: Derek Raymond's Factory Novels by Patrick Millikin in the LA Review of Books

Derek Raymond, The Life and Work by Bruce Wilkinson in the Crime and Detective Stories, Issue 47

The Raymond Revuebar: "A personal tribute to the urban commentary of Robin Cook" by Andrew Stevens

Sarah Weinman's "Reviewing Raymond" in the Guardian. Dated: 10 March 2008

Wikipedia Entry on one Mr. Robin Cook/Derek Raymond. As of 26 May 06, reasonable overview-- with Wikipedia idiosyncratic caveats applicable. Heeeeavy on the Factory; like 60s didn't even exist.

An interview w/ Maxim Jakubowski on topics divers & sundry-- but touching upon the subject of one Mr. Robin Cook/Derek Raymond

San Francisco Chronicle article with some Raymond content-- scroll way down.

DEREK RAYMOND and PATRICK HAMILTON: Drinking in London Through Their Eyes by Cathi Unsworth

Journey to the End of the Night by Cathi Unsworth

My Friend Robin by Maxim Jakubowski

Italian language interview

Intervew w/ John Williams, literary executor of Derek Raymond

He Died With His Eyes Open was adapted by French people into a film entitled On ne meurt que duex fois. amazon.fr link. Amazon.com link. Thanks to Alex Romanelli for the info!

"The 50 Greatest Crime Writers, No 30: Derek Raymond" in The Times. Dated: 17 April 08.

"Dark Voices - The Suarez Seance" by Steve Finbow, via the redoubtable 3:AM Magazine. Dated: 20 July 08.

"Train Noir" an interview with Maxim Jakubowski re: Raymond by Andrew Stevens in 3:AM. dated: 11 August 08.

"Derek Raymond's South Circular" by Andrew Stevens in 3:AM. Dated: 8 November 08.

"Death at One's Elbow: Derek Raymond's Factory Novels" by Charles Taylor, in the Nation. Dated: 17 December 08.

"Derek Raymond's Factory Novels" by Jeff VanderMeer. Dated: 15 May 09.

"Resurrecting Derek Raymond, a.k.a. the first Robin Cook" by Richard Rayner in the LA Times. Dated: 24 June 09.

The unfortunately named "Not Everybody Loves Raymond" by J. Kingston Pierce, on 3 December 09, inaugurating an ambitious and welcome series of reviews of the Factory books. (links above, under appropriate titles.)

Back to top

Back to top

October 9, 1992 / Evening Standard

BOHEMIA is dead. Long live the Chelsea Arts Club Ball. This Sunday, hundreds of bright young things - and bright not-so-young things - will don their fancy-dress finery and step out for a party institution at the Albert Hall that dates back to 1908. Apart from a brief revival in the early Eighties, the Ball rolled to a stop in the Sixties after five decades of annual gonzo partying. Now it is to be revived as a regular event. The title's the same but the proceedings may be entirely different.

In the post-war, ration book, utilitarian, prefab Fifties the ballgoers were real bohemians. Impoverished artists, actors, painters, sculptors, writers and other talented layabouts who lived by their wits and drank cheap wine by the neck. They also smoked. Then, the Chelsea Arts Club Ball meant what it said: a Ball for Chelsea Artists. Then, artists had 'patrons' and Aids were something to put in deaf ears.

Latterly, it has become another good excuse for the hasty convening of a charity committee which smells the potential of money to be distributed among the needy. Proceeds from this year's Ball will go to Aids Crisis Trust and The Chelsea Arts Club Trust. Although it promises to be a grand bash - with the fancy-dress code of coming as your favourite character in a painting - a feeling of worthiness has usurped the uncompromising devotion to hedonism that characterised the Balls of yesteryear.

A more cautious attitude, perhaps second cousin to the profit principle, has slipped past the bouncers. It is going to cost the punter 25 units of our much-sought-after currency just to get through the door, without so much as a plastic mug of Hirondelle.

This sort of approach, of course, enfeebles the whole spirit of the event, since the point about young artists is that they were and are broke, whereas at the ticket price just quoted the only people likely to appear are haggard Euro-wonders, who can be seen not only more or less anywhere but insist on being seen pretty well everywhere, the majority possibly suspecting they will not be around for very long.

There is a difference between what I suspect the atmosphere of the Ball will be this time and the way it was the last time I went, and the comparison is perhaps worth making.

I don't remember leaving the Chelsea Arts Ball in 1958 although I must have done because I woke up next afternoon in a strange house with a brand new girlfriend - things happened suddenly in those days.

I remember arriving quite clearly, though; I went as a playing card, which unfortunately got bent while I was getting out of the taxi. Robert Jacobs was with our little party ('I shall either be Lord Wreningham by the time I'm 30 or else in jail'), also Johnny ('Not All A Ball') Moynihan, a fellow lance-corporal from national service days who was covering the event for In London Last Night.

I had been to his birthday party earlier in the year, which included a game of rounders using champagne bottles for bats on his parents' lawn at 155, just up the street from the Arts Club.

Johnny came simply and delightfully attired as flowers in a pot, accompanied by the gorgeous Rita Wheatley. Much later in the evening I caught him as he reeled away from the telephone outside the dining-room with the last bloom dangling from one ear, murmuring hoarsely as he collapsed: 'Phoned story in - terrific stuff!'

We put him in a corner still clutching the receiver which someone had severed from the rest of the instrument, so that was one scoop which never reached the newsdesk.

The two Roberts, Colquhoun and MacBryde, came as themselves, complete with paint-brushes, palette and oil colours which they mixed assiduously, at times improving, with the sure touch of the master, the costumes of fellow artists whose work they did not like.

The music was almost entirely jazz, with impromptu solos from several of the guests, who after all included Wally Fawkes, Johnny Dankworth and Dizzy Gillespie.

Even Bricktop put in an appearance, flying in from her extraordinary nightspot on the Via Veneto where I had recently had a fight with Paul Anka's Japanese business manager. He hurled himself at me from his wheelchair and won hands down, in spite of having no legs.

In another corner, sitting out Rock Around The Clock while the exhausted band took five, my girlfriend, who had spent days with Nanny getting ready to be Queen of the May, was having a tearful but monotonous argument with a German Fraulein who kept hissing at her: 'But it is not May, darling, it is October!'

West de Wend Fenton, who had arrived as a bottle of vodka ('it meant I could come as myself'), found two old people arguing with each other and knotted their ties together; neither of them noticed until one of them wanted to go to the loo and the other didn't.

What happened to all that? The Ball is on again but however it turns out I shouldn't think it will be the same as in 1958. People say how boring the Fifties were; but I think that what we had going for us then was a dotty but innocent exuberance.

We treated life as a series of pranks, a more or less harmless pastime like village cricket or darts. Of course we had our sprinkling of bores, politically correct prototypes, gruff, pipe-smoking, right-thinking neanderthals of both sexes and so on. Yet what on earth would we have done without them? What other targets would we have had for our seedling epigrams? They were fair game for all.

Besides, we had the luck of happening during the irreplaceable now-you-mustn't-do-that era, so that we had all sorts of irresistible things to rebel against.

But all that has gone, of course, and I don't think people of my children's age, say, are quite sure any more where youth's common enemy is, now that the age of stuffiness and pomposity lies dead at the bottom of its cage, its iron beak still open in a squawk.

How can I point the way to a rediscovery of the days when the pound in your pocket bore no relation to the amount of fun to be had at the Chelsea Arts Ball? Perhaps, as an attitude, West's course was a good one.

After being arrested in 1957 for demolishing a lamp-post in Red Square in his van with a few Stolichnayas on board and being told never to return to the USSR, he told us: 'I thought it over, and then decided to go back as a new person.'

Perhaps one day everybody going to the Chelsea Arts Ball will do the same.

Back to top

The Boston Globe: A Reading Life

Derek Raymond: A writer who went down into darkness

Five or six times in a life you come across a book that sends electric shocks skittering and scorching through the whole of you and radically alters the way in which you perceive the world. There's a great deal of talk about books changing lives. The mass of people are as likely to have their lives changed by a doughnut as by a book. But it does occur.

In 1990, as usual, I was reviewing for a number of periodicals; books arrived daily by the boxful. It became my habit, as I headed out for afternoon coffee, to select a book at random from the stack and take it along.

One day I happened to pick up the unprepossessing trade paperback of a thriller by Derek Raymond titled I Was Dora Suarez.

And for three or four hours, I was. Not only youthful Dora Suarez, who lived and died horribly. I was also taken deeply into the mind of the nameless detective from "the Factory" who, reading Suarez's journal and following her trail through tangled London streets, sets out first to solve then to avenge her murder. And from the first page I was plunged into the mind . terrifyingly into the mind . of the murderer himself. His thoughts and feelings became as real to me as the chair upon which I sit now, writing this. I put down the book stunned. I was sitting outside and, suddenly, quite ordinary traffic along Camp Bowie Boulevard seemed fraught with meaning. Streetlamps came on, dim and trembling in early twilight. I realized that this novel now aslumber on the bistro table before me had carved its way into me the way relentless pain etches itself indelibly upon the body. Derek Raymond was the pseudonymn adopted by Robert Cook, a well-born Englishman who spent a great portion of his life in France. Turning his back on Eton and all his birth class implied, he worked for years at whatever menial jobs or scams came to him, writing all the while, learning the secret life of London the way a cab driver must learn its streets. Soon enough he took the crime novel to heart, taking as his subject the dispossessed and faceless, society's rejects: alcoholics, abused women, prostitutes, petty criminals swarming like pilot fish in the wake of sharks. His life's work culminated in the four Factory novels now seen as clear landmarks in British fiction: He Died with His Eyes Open, The Devil's Home on Leave, How the Dead Live, I Was Dora Suarez.

Derek Raymond recognized the last as his great achievement. In his autobiography The Hidden Files he charted, as writer, much the same seismic response I had experienced as reader.

"Writing Suarez broke me; I see that now. I don't mean that it broke me physically or mentally, although it came near to doing both. But it changed me; it separated out for ever what was living and what was dead....If you go down into the darkness, you must expect it to leave traces on you coming up....I know I wondered half way through Suarez if I would get through . I mean, if my reason would get through....you become what you're writing."

And:

"What is remarkable about I Was Dora Suarez has nothing to do with literature at all; what is remarkable about it is that in its own way and by its own route it struggles after the same message as Christ....the writing of Suarez, though plunging me into evil, became the cause of my seeking to purge what was evil in myself....Suarez was my atonement for fifty years' indifference to the miserable state of this world; it was a terrible journey through my own guilt, and through the guilt of others."

Obviously this is strong stuff, not meant for all. Graphic depictions of violence, coprophagy, necrophilia and mutilation . all are part and parcel. But anyone professing interest in literature truly written from the edge of the human experience, anyone wondering at the limits of the crime novel and of literature itself, must confront this extraordinary novel.

He or she will not have an easy time of it. The Hidden Files was published only in the UK. All the novels are out of print here in the States.

Meanwhile, Derek Raymond occupies much the same position in England as does Jean-Patrick Manchette in France. Manchette salvaged the French crime novel from the bog of police procedurals and colorful tales of Pigalle lowlife into which it had sunk. "The crime novel," he claimed, "is the great moral literature of our time." For Manchette and his followers the crime novel became not mere entertainment, but a means to strip bare and underscore society's failures. Derek Raymond, godfather of the new UK crime novel, who despite his many years in the French language always spoke of the noir novel as the black novel, was in full accord. The black novel shows that the world is never what we in ignorance and denial claim it to be, never what we adamantly insist it is to others and ourselves.

"The black novel...describes men and women whom circumstances have pushed too far, people whom existence has bent and deformed. It deals with the question of turning a small, frightened battle with oneself into a much greater struggle . the universal human struggle against the general contract, whose terms are unfillable, and where defeat is certain."

The black novelist's characters, those of I Was Dora Suarez primary among them, forever step from rented rooms and wretched tenements "into the vile psychic weather outside their front doors where everything and everyone has been been flattened by a pitiless rain that falls from the souls of the people out there," theirs included.

Novels like I Was Dora Suarez, Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian and Poppy Z. Brite's Exquisite Corpse bring us in one hand that rain and in the other a shelter against it. There's no question that our highest literature can deal with a young woman's decision to marry, with a young academic's coming of age, or with four decades in a car dealer's life. But also, eventuslly, it must deal with a guard's offhand remark at Auschwitz: Hier ist kein Warum.

There is no why here.

Crime

by Newgate Callendar / nytimes

May 3, 1987

The search for really good paperback crime novels can have its rewads and one of them is HE DIED WITH HIS EYES OPEN by Derek Raymond (Available Press/Ballantine, $4.95). Mr. Raymond, a British author, writes about an unnamed Scotland Yard sergeant who works in what is called the Factory. In the Factory uninteresting murders are investigated, that is, murders of derelicts or hop-heads, or anything that does not interest the Serious Crimes Division.

Our unnamed sergeant is a loner who is tough, honest, experience and prickly. He has no hesitation telling the top brass where to head in. That is one reason he will never advance beyond sergeant. In .He Died With His Eyes Open.he has a brutal murder on his hands. A man has been beaten to death. All that he has left behind are cassettes and writings in which he talks about himself. These relics of a life are woven into the narrative. They are sensitive and even poetic, and the sergeant identifies with the man. Getting the killer, or killers, becomes a personal vendetta.

The book is beautifully written, grimy as some of the characters are. Mr. Raymond is a master of the sharp vignette, the telling phrase, the speech patterns that perfectly describe a character. All of the people in his book are vividly alive. Except for the dead man, they are not high in the social order, and their speech takes some getting used to. It is too bad that the author has not provided a glossary of British slang, so often (and effectively) is it used.

There are two other novels in the series..The Devil.s Home on Leave. and .How the Dead Live..which will also be published by Ballantine. If they are as good as this one, they will be worth having.

Crime

by Marilyn Stasio / nytimes

Nov 4, 1990

If you think of the act of writing as a game of chicken between the author and his talent, then Derek Raymond is one author who achieves his ecstasy by sailing off cliffs.

Everything about I WAS DORA SUAREZ (Available Press/Ballantine, Aper, $7.95) shrieks of the joy and pain of going too far. No. 4 in the English writers. procedural series about an unnamed detective.s garbage-detail job in London.s Bureau of Unexplained Deaths, this hair-raising narrative opens in the midst of a double murder whose graphic horrors would be unreadable were it not for the author.s unflinching insights into the killer.s madness . glimpsed through .eyes that had perished violently centuries ago. . and for the appalling beauty of the prose. Just as there are no limits to the vileness of the crimes uncovered during the police investigation, which leads to a nightclub that traffics in loathsome debaucheries, so, too, there is no bottom to the detective.s rage and anguish.

.Do you know I cry in my sleep.? demands this mournful witness to the inhumanity he sees throughout society. .My tears were not for me,. he makes clear, .They were for the rightful fury of the people.. Truth to tell, the life of Dora Suarez would move anyone to tears. .I was constructed to have a nature that could neither bend nor speak, nor be of a kind to as for help," the murdered woman wrote in her journal. "I wanted to keep my sense of my own dignity, but it is the most difficult thing of all to keep when you are poor..

Touched by her story, the detective kisses the dead woman.s hair and makes the only promise he can make to her and to all other violated human beings: retribution and respect. .We.ll get out dignity back,. he swears to the victims; .whether alive or dead, we shall all be as we used to be.. No less obsessive than the maniacal killer he is stalking, the detective employs methods that are brutal and probably illegal. But there is something angelic about his fierce sense of justice.

Derek Raymond, 63, a Writer of Dark, Graphic Crime Fiction (Obituary)

August 3, 1994 / nytimes

Robin Cook, an English writer who wrote under the pseudonym Derek Raymond and who won a loyal following with his dark and brutally graphic crime novels, died on Saturday in London, where he lived. He was 63 and also had a home in France.

The cause was cancer, according to Reuters, the British news agency.

His first novel, .The Crust on Its Uppers,. published in 1962 under his own name, grew out of his experiences as a young man who rebelled against his middle-class background and went to work for gangsters from the East End of London. That book and his other early novels, including .Bombe Surprise. and .The Legacy of the Stuff Upper Lip,. quickly gained a cult following.

His later novels, including .He Died With His Eyes Open,. .the Devil.s Home on leave,. .How the Dead Live. and .I Was Dora Suarez,. were written under his pseudonym, which he said he took to avoid confusion between himself and another Robin Cook, the author of .Come,. .Terminal. and other books.

Mr. Cook.s fiction grew out of his diverse experiences, which included associations with small-time criminals, dissidents and others who led unconventional lives. A son of a textile magnate, he was born in London in 1931 and named Robert William Arthur Cook. After attending Eton, he worked as a front for a gangster.s real-estate companies, and he combined writing with stints as a pornographer and an organizer of illegal gambling. He also drove a taxi while unsuccessfully trying to earn a living as a writer.

Mr. Cook, whose five marriages ended in divorce, moved to France after his third marriage broke up and worked as a farm laborer. On his return to London, and to writing novels, he completed .He Died With His Eyes Open,. which was published in 1984. The book first became a success in France, which in 1991 named him a Chevalier of Arts and Letters.

His memoir, .Hidden Files,. was published in 1992, and his last novel, .Not Till the Red Fog Rises,. is to be published this fall.

He is survived by a son, Sebastian, and a daughter, Zoe.

Murder disturbs quiet of Pigeon Fork, Ky.

Judith Kreiner; THE WASHINGTON TIMES

November 12, 1990

If you have a weak stomach, you do not, repeat not want to pick up Derek Raymond's latest, I Was Dora Suarez (Available Press, $7.95, 216 pages). It starts with an ax murder. Actually, it starts with a little old lady being thrown through a grandfather clock, but that's by the by. It's a very loving ax murder, lovingly, graphically described.

It's another of Mr. Raymond's Factory series, gritty, unpleasant and somehow ultimately unsatisfying. This one's for his fans.

The Sunday Times

December 9, 1990

After last week's story about the psycho-horror imaginings of Bret Easton Ellis, here's an English follow-up. Robin Cook, the Old Etonian ex-minicab driver and chronicler of the underbelly of society in the 1960s (with titles such as A Crust on Its Uppers), has for many years been publishing, under the nom de plume Derek Raymond, a series of gruesome thrillers known as the ''Factory'' novels. But his latest ''super noir'' gem, entitled I Was Dora Suarez, reaches such peaks of violence and sexual malpractice that his publisher, the adventurous Dan Franklin at Secker, could not read it without feeling queasy. ''I was told he actually threw up,'' cackles the beret-wearing Cook from his Paris flat, ''after which he felt he couldn't look his sales force in the eye and ask them to sell it. So I was told to take it elsewhere.'' I trust the shadow spokesman for health is untroubled by his namesake's disgrace.

O.E. can stand for distinctly Outre Evil

Chris Petit / The Times

December 13, 1990

DEREK RAYMOND began life as Robin Cook, and under that name published low-life novels in the Sixties, including A Crust On Its Uppers, a chronicle of ex-public school boys gone bad, and an important slang source for Fowler. Cook, an old Etonian and skinny Chelsea rake, dropped out in the Seventies, then resurfaced in 1984 with a new name to distinguish him from the American, Robin ''Coma'' Cook.

As Raymond, Cook has written three startling policiers, each progressively less concerned with the procedural business of murder investigations beyond a grisly relish for forensic detail than with London's dank moral decay, and with obsessive meditations on the nature of evil: a demented territory closer to Brady and Hindley than the conventional body-in-the-library stuff. In Raymond's last novel, How The Dead Live, his narrator an anti-social, insubordinate, unnamed copper travelled well beyond the usual boundaries of the crimethriller format into landscapes more associated with Edgar Allan Poe. It was the clearest statement of the central paradox in Raymond's work that the dead live and the living are in a sense dead.

A recurring device in the novels is some record left behind by the dead, awaiting interpretation. In I Was Dora Suarez it is the diary fragments of a prostitute brutally hacked to death in a grim Kensington flat. As usual with Raymond, the scene of the crime holds an almost mystical significance, seen here first through the eyes of the killer, then by his investigator, called in after the brutal double-murder laconically announced by the opening sentence: ''Interrupted by her because she had come to see what was happening next door while he was still finishing up with the girl, the killer came up to the old woman without a word, got hold of her as if she were a load of last week's old rubbish and hurled her through the front of the grandfather clock which stood just inside the door of the flat, using strength that even he didn't know he had.''

In an extraordinarily sustained piece of writing, Raymond first charts the psychopathology of the murderer, then attempts to identify the nature of that violence. In doing so, he shows increasing impatience with the conventions of the genre. The plot has the flimsiness of a B-movie scenario a Soho club with an inner sanctum that specialises in the most depraved entertainment imaginable and the routine leg-work interests him much less than his bizarre immersion into, and indentification with, the tortured worlds of the killer and victim. With the latter, this verges on the necromantic, so much so that Raymond's detective now seems more at ease as a medium for the dead than in communication with the living, who are greeted with a splenetic, barely controlled rage. The result is a book full of coagulating disgust and compassion for the world's contamination, disease and mutilation, all dwelt on with a feverish, metaphysical intensity that recalls Donne and the Jacobeans more than any of Raymond's contemporaries. I cannot think of another work in this field so obsessed with the skull beneath the skin.

Murder most foul and pulp most messy; 'I was Dora Suarez'

HUGO BARNACLE

January 5, 1991

DEREK RAYMOND's work is much admired in France, where he lives, and in its overblown, careless style and Chandleresque pretensions it strongly resembles the nastier kind of comic strip policier you can buy on boul' Mich'.

By a painful irony, the lovely Dora, dying of Aids, had planned to put her head in the oven and end it all with dignity on the very evening her psychopathic lover chopped her up with a fire axe. We know this because the nameless investigating detective, our narrator, reports the contents of her diary to a colleague on page 44. Unfortunately, Raymond neglects to have him discover the diary in a kitchen cupboard until later that morning, on page 49, or to open and read it until he gets back to the office later still, on page 54.

The ground rules of good composition are pretty well set aside at the outset, when the detective treats us to an omniscient blow- by-blow account of Dora's murder from the killer's point of view, complete with dialogue, flashback and stream of consciousness. Call me Tiresias, he seems to say.

The killer, having also dealt with Dora's aged landlady, later shoots a Soho club owner with a 9mm automatic which Raymond thinks is ''big''. Here Sergeant Tiresias goes one better and gives us the victim's viewpoint too, before lingering for a full page on a slo- mo description of the man's head exploding. Only the bottom jaw is left, tongue slithering over gold fillings while brains and snot coat the wallpaper. In fact, 9mm pistol ammunition cannot produce this effect or anything like it. It would take an anvil swung from a crane or, as here, just a very crude imagination.

The detective visits the morgue to study Dora's Aids symptoms, then gets on with cracking the case. He does this mainly by interrogating the club management, which takes up most of the book: the bright light, the threats of Maidstone and all its horrors, the burly sergeants flexing their muscles in the corner.

You half expect Michael Palin in a scarlet cassock, bringing on the Comfy Chair, but the gangsters crumple and their sinister gerbils racket is exposed. (That's right: gerbils.)

The action opens on 26 February this year and closes on 1 March, we are told. The days and nights between do not quite add up, to say the least. At one point the detective leaves the office in the small hours, walks to a gambling den where it is still mid-afternoon (with the 3.30 at Kempton Park just starting on TV) and returns to the office around dawn an hour later. During the morgue scene several pages are printed in the wrong order and it scarcely shows, the whole thing is so disoriented.

The air of unreality is heightened by the detective's falling in love with Dora, whom he never knew. Her allure, of course, is that she is safely dead, but although this sentimental misogyny is routine for pulp fiction Raymond voices it with amazingly blatant unselfconsciousness. After her ''collops'' of hewn flesh hit the carpet in close-up, then he gets all lovey-dovey. The killer masturbates over her corpse explicitly, but the detective and the author seem to be into much the same thing.

The killer's psychopathic state is quite well caught, his ''illusion of living: everyone who detected that it was in fact nothing but an illusion had to go''. Raymond does better, though, with the detective's ex-wife, now in the bin for killing their daughter: ''she was never sincere with me about anything, but responded to any approach I made to her with a perfunctory sweetness . . . she was immersed solely in thoughts of hatred and new curtains''. That is a psychopath to the life, but nothing else in the book argues such perception.

Along with the obligatory punchyish epithets - the sun ''the colour of a fake guinea'', the noise of London ''like a gagged man trying to speak'' - goes the pulp convention that fantasies of ''front line'' low-life constitute withering social comment. But Britain's real social ills are unlikely to be shown up by an expat writer who thinks that the ''national assistance'' provides free winter clothing, and who does not even know that London switched to non-toxic natural gas some 20 years ago.

Whodunit? The author, of course

Margaret Park / The Times

August 5, 1992

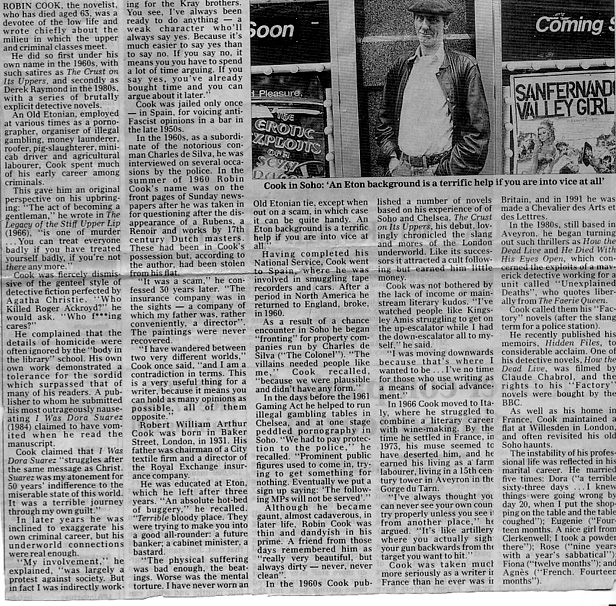

Crime writer Derek Raymond reveals his real name and an extraordinary history, when questioned by Margaret Park

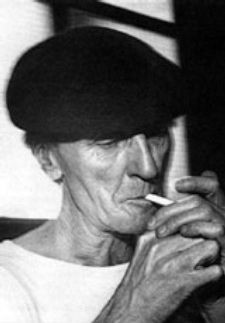

Robin Cook is emaciated in the way heavy drinkers often are. He sits alone at a small table in a Soho pub, looking frail, with the sleeves of his shirt rolled up high to expose thin, white arms, and a black beret jammed like a peaked cap onto the front of his head. It is 2pm, but Cook has not been up long. He writes at night. This morning he emerged from his current struggle with death and depravity a novel he calls Dead Man Upright at 7am, slept for four hours and then, as normal, set off for the ''Coach''.

To readers of crime fiction, Robin Cook is Derek Raymond, author of 11 exceptionally bloodthirsty novels. The BBC has just begun dramatising the four most recent, which will be turned into a drama series called Dead at Night for broadcast next year. It is hard to imagine how the stories will be made fit for screening. Cook writes with a stomach-churning exactness about murder, madness and mutilation. His stories are peopled with psychopaths. Unspeakable acts take place in the upstairs rooms of vice clubs. In his last book, I was Dora Suarez, the killer follows a detailed dismemberment by axe with a spot of self-mutilation which leaves a vital organ shredded to a pulp.

Clearly, this is not everyone's taste. At least one publisher refused to touch it. ''Threw up all over his desk, apparently,'' says Cook, with evident glee. At 61 he speaks with the exaggerated vowels of wartime Eton, a complete contrast to his gap-toothed, dishevelled appearance.

Why would anyone want to write such horror? The answer, dropped obliquely into his conversation, is that Cook is writing about his own life. He admits he has been ''involved'' with more than one murder, but declines to explain how. ''That's what I've tried not to say in my memoirs,'' he says lightly, shaking another Gitane from his packet.

The memoirs, entitled Hidden Files, in which he remembers very little about himself altogether, are published this month. The book is principally a dissertation on what he calls the ''black novel'', and apart from descriptions of a childhood marked by a mutual loathing between himself and his wealthy parents, reveals frustratingly little about Cook's past. There are tantalising glimpses of an early life of crime, the scams financed by East End thugs and fronted by young drop-outs from Eton; the five wives (the last divorce recently completed); a first novel at the age of 31; the years in which he chose to be a farm labourer in France and Italy; and constant restlessness during 40 years spent in at least nine countries.

From the day he got his nanny sacked by running away, Cook has been disliked, it seems, by pretty well everybody close to him. He reckons that, mentally at least, he dropped out of his silver-spoon existence at the age of about three. ''I thought God, what awful cards have I drawn here? I couldn't wait to get out of it. I've always been on the downward staircase watching everybody else on the upward one.''

He may have stepped away from the physical trappings of his class but he has not shaken off the upper-middle-class belief that it is not quite right to talk about oneself. Cook prefers to believe it was a later training that made him cautious: ''When you work for the underworld, you very soon learn to keep it buttoned,'' he says sternly, drawing a line sharply across his mouth.

This is an odd stance from which to write an autobiography. But Cook seems surprised at the criticism. ''It's a book about writing,'' he says. ''If you don't talk about writing there wouldn't be much to talk about. There would just be one boring anecdote after another.''

The anecdotes he does allow himself include the fake property company in the Sixties: Cook was the nominal managing director. It was his job to persuade banks and members of the public to invest in housebuilding on the south coast. No houses were ever built. The money was collected weekly by his employers: East End gangsters in Rolls-Royces.

Later Cook got himself arrested after several paintings, apparently given to him by a friend to sell, disappeared in Amsterdam. He was grilled for 17 hours by police working shifts around him. It was an experience that still amuses him.

This part of his life is described to some extent in his first novel, The Crust on its Uppers, which is reissued this month. First published in 1962, the novel is written in a Fifties' street slang which is so peculiar to its time that the book contains a glossary.

Much more of Cook, then, is in his novels than in his autobiography and he makes the violence of the former sound like a necessary catharsis: ''What I'm doing, constantly, is trying to see how far I would be capable of doing such things myself,'' he says emphatically. ''If I didn't think I was capable of something fairly considerable I wouldn't be writing like this, because the point of these books is to be as honest as you can.''

Partly because of this unbroadcastable honesty, the BBC has bought the rights not to the novels but to the principal character in the later books, a manic-depressive detective sergeant who is never named. Like Cook, his detective has a special knowledge of crime: his wife is in a mental asylum after murdering their child. Not surprisingly, the detective is an obsessive, a policeman with no interest in promotion or reward, with an urge to plunge into the minds of the killers he pursues and a loosening grasp of the difference between law and criminality in his own actions.

Perhaps Cook's affection-starved childhood was a little like the disturbed infancy that is supposed to produce the psychopathic killer? ''Wasn't it,'' he agrees with some satisfaction, his large, sunken eyes widening. ''And I think that's the link. The difference is I managed to find my way out of it by other means, thank God.''

Cook is less celebrated in Britain than in France, where he was made a Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres last year. The French director Claude Chabrol is filming How the Dead Live, his ninth book, with Philippe Noiret in the leading role.

''My readers are invariably people who are fascinated with the truth,'' he says, waving another Gitane. ''My greatest fans are nearly always people who've done time in jail or led very difficult, dodgy, hard lives.''

Hidden Files is published on August 13 (Scribners, Pounds 14.99), and The Crust on its Uppers is reissued on August 27 (Scribners, Pounds 7.99)

A tough old cookie

y CHRIS PEACHMENT / The Independent August 16, 1992

WHEN I met Robin Cook, alias crime writer Derek Raymond, at lunchtime in The Coach and Horses, he was already at the bottom of a pint of beer, and was chatting up a pretty woman. Down here in Soho, his twin appetites are legendary. One recent interviewer stayed longer in his company than intended and finally slid silently under the table; Cook, just hitting his stride, had to scrape him up and get him into a cab. When I first met him four years ago, he confided that he had spent the best part of his life in pubs. ''I fear it is beginning to show on my face,'' he said. Well, he said it.

The face is indeed cadaverous, and his teeth are medieval. But, at 61, at least he is as skinny as a polo mallet, without the jowls and busted veins of the dedicated piss-artist. Food seems a minor inconvenience in his life. We are toying with some Dim Sum in a Chinese restaurant, and he is chain-smoking Gauloises, not just between the courses, but during them. It's a pleasure to be with someone so politically incorrect.

He is wearing a T-shirt advertising the Black Lizard thriller imprint. And it is topped off with his familiar beret, like an old 45rpm record that fell on his head and melted. Altogether he looks like a death mask on stilts. Yet the women still keep coming, crashing through his upper decks like kamikaze pilots. He has been six times married, for lengths of time varying between 63 days and nine years ''with a bit of a break''. His habit of referring to them as ''No 2'' or ''No 4'' is endearing; as are his courtship habits - ''Stole that one from the poet Bernard Gutteridge. Shouldn't have done it really.''

The gory details are now available, along with a load of theory about what he calls the ''black novel'' - which seems to mean just about any writing he approves of - in his autobiography The Hidden Files.

Lately he has been a bit worried about the state of his liver. A Parisian doctor warned him that if he continued drinking on his usual heroic scale, he would only have five years to live. ''Had to pay him 90 quid for that news,'' says Cook. ''If I'd paid him 150 quid, he probably would have given me two years.'' He adds with some pride that the doctor had just returned from a stint with Medecins Sans Frontieres in Afganistan, and had seen nothing on the battlefield as bad as Cook's liver. ''So I laid off the drink for six months,'' he says, ''No problem. It's just so bloody boring.'' He sticks to beer and wine these days, although a mutual friend claims to have seen him sink 12 pints at a recent sitting.

He quit Eton in 1947, aged 16, with a bitter hatred of the place and the class from which he came. ''Only man who hated it as much as me was Orwell,'' he says. ''Absolutely vile place. Hotbed of vice.'' But in a post- war Britain stuck in its pre-war habits, revolt and classlessness were not quite the thing. After a stint as a corporal latrine-digger in a tank regiment, Cook went abroad and took to smuggling: paintings to Amsterdam, fast motors into Spain from Gibraltar, tape recorders wherever.

When he returned to the King's Road in the Sixties, he found a milieu much more to his liking. Donning his Chelsea boots, sheepskin coat and shades, he became a front man for various ''property companies'' run by one Charlie Da Silva, a man not unknown to the Krays. ''I had a plausible manner,'' he says.

The Cardinal and the Corpse, a forthcoming film for Channel 4 by Chris Petit and Iain Sinclair, about the search for a possibly non-existent rare book, features Cook, as himself, back in the company of such Sixties ''morries'' (Cookspeak for ''characters'') as Emmanuel Litvinoff and Tony Lambrianou, a ''driver'' for the Krays. ''Used to know Litvinoff's half-brother David quite well. He managed to kill himself. Which was probably just before he would have been murdered.''

Inquiries as to the exact nature of David Litvinoff's offence are hedged around with euphemism. ''Well, as the French say: 'He lost his pedals in a serious manner.' Great bicycling nation, the French.'' History records that the Krays grew tired of Litvinoff, strung him up by his ankles and cut his throat so badly he needed 170 stitches. What they failed to achieve he did for himself. in a house later bought by Bob Geldof.

Mere mention of Lambrianou, celebrated author of Inside the Firm, still turns Cook pale. ''They finally sent him down for transporting a corpse for the Krays. Couldn't pin anything else on him.'' It was Jack the Hat, and Lambrianou did life. He's out now, and still peddling tales of Reggie's great sense of humour.

This life on the edge of things, including a stint as a pornographer in St Anne's Court, finds its way into an extraordinary sequence of half a dozen near-autobiographical novels of bad manners which deserve better than the ''cult'' label usually attached to them. The mods had Colin MacInnes; the posh tearaways of ''swinging London'' got Robin Cook.

The Crust on Its Uppers, Private Parts and Public Places, Bombe Surprise and State of Denmark offer a leery anatomisation of that rag-trade con, the Sixties, and the criminal behaviour at the heart of that louche decade. The Crust on its Uppers is as inventive in its use of underworld argot as anything by Anthony Burgess; it was recommended by Eric Partridge as the best source of slang in the last 25 years. The critics used to consign this form of writing to an ''underclass'' of literature, but Cook gives a better account of his era than any other novelist. You won't find his pornographers, Fascists, tarts, chancers and rent boys in the likes of Murdoch or Drabble. He saw through the squalid con of that time and pinned it down with misanthropic relish.

He left the country in the Seventies for reasons a shade obscure, although not hard to guess at. When a man keeps the sort of company he kept, then there comes a point when he must look after his ''health''. He settled in a tower in Aveyron, to the north of Montpellier, and began working as a vineyard labourer. This, at a time of life when most men are sinking into a sedentary middle age.

''It did keep me very fit,'' says Cook, indicating the skeletal thinness of his body. ''But one day someone in the village said to me: 'You are going to end your days as a labourer.' I was 48, and I tell you, that comment hit me where I lived.''

So he began writing again, about a nameless south London detective, a highly moral man with a vicious temper and a strong sense of justice, who pursues all the old murder cases from the ''dead files'' which no other copper can be bothered with. For the thrillers, Cook adopted the nom de plume Derek Raymond, because he doesn't want to be confused with the other Robin Cook, best-selling author of Coma and other airport dross, ''nor with the bloody shadow minister for health, come to that''.

The books cover the streets of Lewisham and Acton, but are not exactly realistic. The true world they inhabit is a place of stark moral contrasts that stinks of decay and cheap death. The Devil's Home on Leave is about a hitman who has been thrown out of the army in Belfast, and is running around London boiling his victims in a big vat.

The series is a success in France, and they have filmed both He Died with His Eyes Open, with Michel Serrault and Charlotte Rampling, and The Devil's Home on Leave, seen on French television. Cook regrets that they weren't set in their proper south London milieu, although this may be put to rights shortly by a three-part series, on its way from Kenith Trodd at the BBC. Also in the future is a projected film by Claude Chabrol of How the Dead Live, with Philippe Noiret pencilled in as the policeman.

It is unlikely that anyone will manage to film his last book, I Was Dora Suarez, a chronically disturbed meditation on the psychology of a serial killer. I am not the only reader who did not have the stomach to finish the book's catalogue of torture, cannibalism and degradation.

''Can't blame you, my dear fellow,'' says Cook very kindly. ''It cost me a lot to write that book. But I refused to pretty it up. I am sick to death of a certain kind of genteel British thriller writer for whom murder is just a hobby. It ain't. It's a barbarous, horrible business.'' One wonders how close to the act he has ever come. ''You couldn't write about it properly unless you have been violently tempted to kill someone in the past. Which I have.'' So what stopped him? ''Just some strong moral sense, which says to me: Mustn't do that, Cookey, that's wrong.''

He writes at night, and confesses to having been at it all last night until seven this morning, polishing his next one, Dead Man Upright. It is now four in the afternoon and he is still going strong. By five we are still discussing the people he has known around Soho: Henrietta Moraes, Francis Bacon, Daniel Farson, Johnny Minton, all the usual suspects. Also the little-known novelist Veronica Hull, author of The Monkey Puzzle, a roman a clef which caused a scandal in the Fifties by lifting the lid on Freddie Ayer's activities with his female students.

''Trouble was, she had a brain like a bandsaw. Lived with her for two years. I was one of her few survivors.''

By six, it is time to part; he back to the Coach and Horses, me in search of an iron lung. ''I know I am a set of complete contradictions. And if I hadn't been a writer I would have gone mad from it all. But I still look around, and at myself, and I think: What am I doing here? Shan't stay long.''

'The Hidden Files' is published next week by Little, Brown, at pounds 15.99.

DOWN AMONG THE DEAD; Derek Raymond's detective is a crusader in a bleak and uncompromising world without morality or hope

ELIZABETH YOUNG / The Guardian

December 3, 1993

AN OLD woman is hurled out of a north-bound car to die on the hard shoulder of the M1 as the night rain washes over her. A Ford assembly line worker butchers a child on a Nonwell estate. A pensioner and a Spanish prostitute perish together in a decaying Empire Gate mansion block. These are the sort of deaths that do not interest any one very much. They rarely make the papers. They hold no opportunities for promotion. They are the murders that the unnamed narrator of Derek Raymond's Factory series of detective novels investigates. This man, embittered and humane, works out of a West End police station - the "Factory". Working for a department called "Unexplained Deaths" he sees all around him wreckage, waste and agony.

These are hellishly bleak and desolate novels. They turn over London as if it were some vast refuse tip, revealing all its most scarred and God-forsaken corners, its most rancid and pitiful secrets. They are powerfully compassionate books in which the narrator seeks justice for the most loveless and wretched of the city's inhabitants. They belong recognisably to the Chandleresque genre of noir fiction and film, which helps to explain why the novels are so highly esteemed in France. In Britain they are heirs to the less familiar territory of Patrick Hamilton and Gerald Kersh.

The first Factory novel He Died With His Eyes Open appeared in 1984 and the fifth in the series, Dead Man Upright, has just been published. The four most recent books are being dramatised for a series, Dead At Night, which will appear on the BBC next year.

Many of the observations in the novels are based on personal experience. Derek Raymond's real name is Robin Cook. An entertaining, haunted-looking man, he has served on the bohemian front line for decades and is an habitue of the Coach and Horses in Soho.

Born in 1931, Cook always detested his privileged background. He walked out of Eton. He was, he wrote, someone "who was sick of the dead-on-its-feet upper crust he was born into, that he didn't believe in, didn't want, whose values were meaningless". He was seeking to carve his way out and "crime was the only chisel I could find."

Cook joined various other upper-class rakes who were beginning to assault the rigid, seemingly entrenched icebergs of polite British society. These were razor-sharp fifties wide-boys, artful dodgers of whom British gonzo journalist Nik Cohn wrote: "It became chic to cut corners, to gamble and dabble in illegalities and carry an air of mystery, to know gangsters by their first name."

Although Cook was closely involved with a number of criminal enterprises - "I was bent, that's all" - he had enough detachment to write a series of satirical novels about those days. The first and best-known of these was The Crust On Its Uppers, originally published in 1962 and reissued last year by Serpent's Tail. Cook eventually wandered abroad but completed two years as a London mini-cab driver before settling in France in 1974.

In France, Cook worked at a number of desperate, dead-end jobs - as a roofer, as a driver, in vineyards - and wrote nothing for a long time. "I'd been working on the land for five years when I wrote He Died With His Eyes Open," he says. "One of my neighbours said to me 'You're fucked. You're 48. Call yourself a writer? You'll be a day labourer for the rest of your life.' It hit me and I thought 'Come on, see if it will still work'."

He says that he intended the book to be a one-off and that it was largely autobiographical. In retrospect it is an ironic book. The detective narrator is seeking the murderer of a man who initially appears to be little more than an alcoholic dosser. The character of this victim corresponds closely to Cook's own. The book was very well received and his publisher encouraged him to follow it up. Thus it was, having effectively killed himself off, Cook emerged with a new writing career, a new identity as Derek Raymond and a huge number of new fans.

It was I Was Dora Suarez, the fourth book in the Factory series I Was Dora - over which a publisher memorably lost his lunch ("threw up all over his desk apparently") - which was to bring Cook real notoriety and renown. Painful to read, it was carefully researched and the writing of it caused Cook great distress.

Its poor, doomed victim, Dora, is an Aids sufferer, working in a private sex club where much of the erotic entertainment features small rodents inserted into the anus. Her killer, Tony Spavento, is not only so sexually disturbed that he kills others but also ritually mutilates himself. Many of these details Cook obtained from police reports. Throughout the Factory series Cook had shown an increasing interest in the psychology of the psychopathic murderer, and in his autobiography The Hidden Files, published last year, he discussed the "vile psychic weather" of his novels.

No serious novelist can animate evil without having a profound belief in its opposite. "Tenderness, compassion," he says, "if you haven't any of that you might as well not bother writing novels at all." It is this sense of pity and of pathos that most deeply characterises his books. His most recent novel, Dead Man Upright, is virtually a textbook of sexual psychopathology. Cook says that he has met psychopaths and "they were flat. There was no reaching them. There's a dimension missing. There's no depth." Ultimately such blankness and self-absorption can only stun the imagination and Cook now intends to take the Factory series in a different direction.

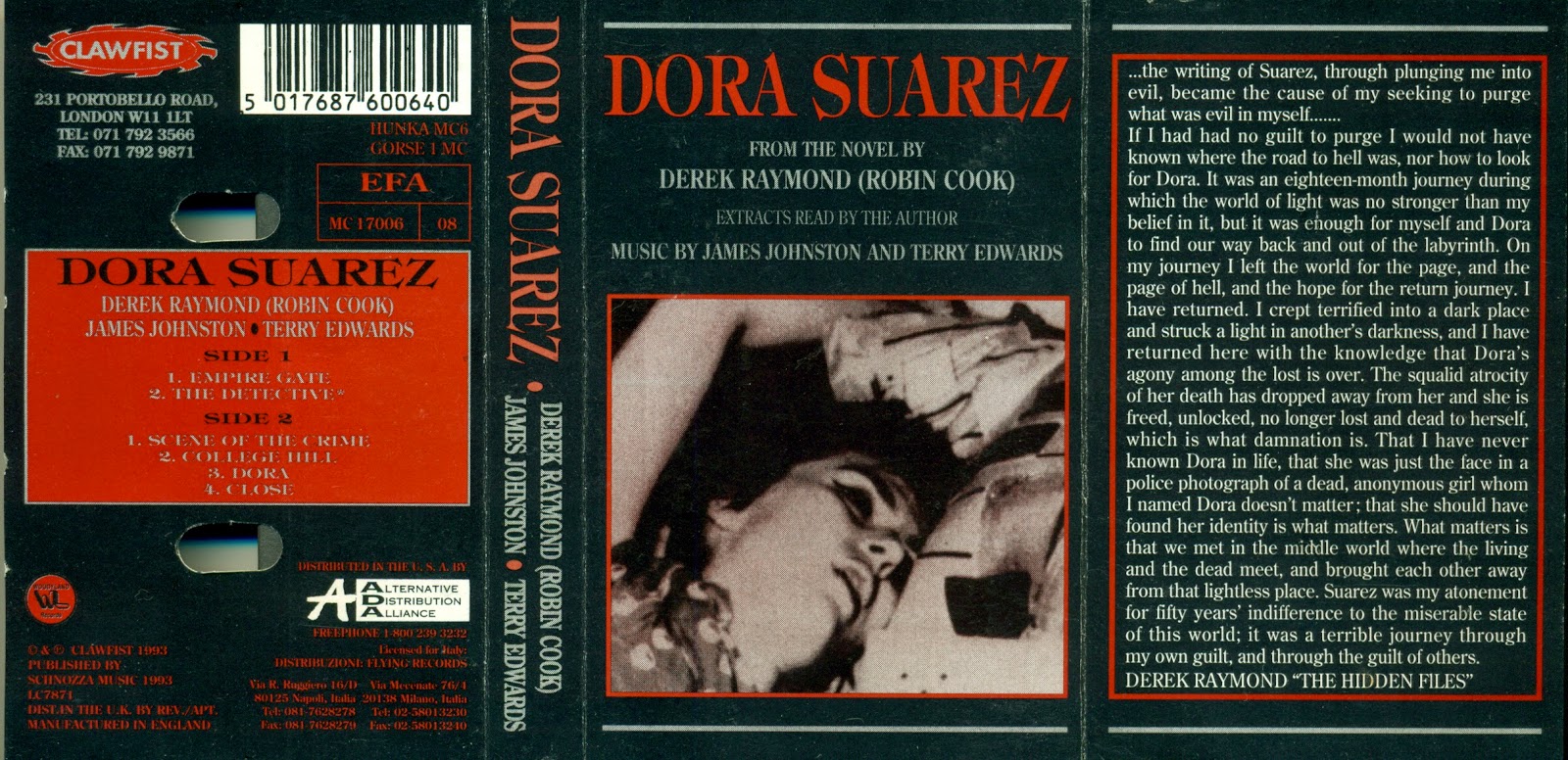

Cook's most recent venture has been more unusual. In the wake of Hubert Selby's work with Henry Rollins and William Burroughs's recordings with The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprasy, he has been involved in recording extracts from I Was Dora Suarez with a musical score by James Johnston and Terry Edwards, two members of London band Gallon Drunk.

Gallon Drunk's last album, From The Heart Of Town, showed a preoccupation with the seedy world of London's dispossessed very similar to Cook's own. Lyricist James Johnston works not unlike Cook, picking up fragments of conversations from street and bars. Johnston was already a fan of Cook's work and stresses how much he enjoyed supplementing the text "in the most subtle ways possible". Terry Edwards initially found the project more troubling, saying that his original reaction to the book was "shock and horror. The murders are graphically portrayed and it's very disturbing." Edwards was also concerned about the focus on sexual violence and the way the book had to be extensively edited. Little is left but the murders and the policeman's revenge - a very violent revenge carried out, as Edwards says, "on a severely mentally disturbed person. However I've spoken with Robin about this and the idea is that evil permeates good, that it permeates the detective and he becomes as mad as the killer."

Cook was initially taken aback at the idea of reading to music. He describes his voice as being "like an iron parrot". However his reading poignantly conveys the pain and bewilderment of the novel, and the music, which is simple and plangent, communicates the ambience so effectively that the aural version is very much more affecting than the written one - and it is a very strong and alarming piece of work.

Cook, Edwards and Johnston met originally in the Coach and Horses and seem to have been there for some time now, leaving journalists with interview tapes that have to be held to the ear like an alcoholic seashell. All three are happy with the final collaboration. Cook was particularly pleased at their interest in his work and the fact that there seemed "to be no age gap at all" - which means he has been attracting disaffected bohemian readers for over 30 years now.

Dead Man Upright is published by Little Brown, pounds 15.99. The CD of Dora Suarez from the novel, I Was Dora Suarez, with music by James Johnston and Terry Edwards is on Clawfist Records. Derek Raymond/Robin Cook will be signing copies of his new book on December 9 at Murder One, 71 Charing Cross Road, WC2, at 6pm.

Obituary: Robin Cook

JOHN WILLIAMS / The Independent

August 2, 1994

Robert William Arthur Cook (Derek Raymond), writer: born London 12 June 1931; five times married (one son, one daughter); died London 30 July 1994.

THE NOVELS written by Robin Cook under the pseudonym Derek Raymond stand alone in contemporary crime fiction.

He is not recognisably linked to the main British school, the cosy ''country house'' tradition. More surprisingly, since his main protagonist is a detective sergeant, neither does he have anything in common with the police procedural tradition. Cook did not merely bend the rules of crime writing, he ignored them entirely. If he compares to any other crime writer, it is perhaps Jim Thompson, with whom he shares an unsettling ability to evoke the mind set of a psychopath. Otherwise he relates stylistically perhaps only to Patrick Hamilton, author of Hangover Square; but he never had Hamilton's limited faith in Marxism. Instead, Cook was ultimately a tortured moralist, obsessed with the twin questions: why do people suffer, and why does evil exist?

Robin Cook was born in London in 1931, the eldest son of a textile magnate. He spent his early years at the family's London house, off Baker Street, tormenting a series of nannies. At the outbreak of the Second World War the family retreated to the countryside, to a house near their Kentish castle. In 1944 Cook went to Eton, from which august institution he removed himself at the age of 17. A period of National Service followed, in which Cook once again distinguished himself, as one of the few Old Etonians to come out of the army with the exalted rank of corporal (latrines).

The army years instilled a thoroughgoing penchant for downward mobility. A brief stint working for the family business (selling lingerie in a department store in Neath, South Wales) convinced him it was time to see the world, and he spent most of the Fifties abroad. In Paris he lived in the ''Beat Hotel'' alongside William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, dancing with the likes of Juliette Greco in left-bank boites. In New York he lived on the Lower East Side with the junkies and the jazz musicians, dating girls from Harlem and heiresses from New England (even - briefly - marrying one of the latter). And in Spain he encountered poverty beyond anything he had known and spent time in jail for sounding off about Franco in his local bar.

He returned to London in 1960, making it to the French Pub in Soho with sixpence left in his pocket. There he found that the town had blown wide open in his absence. The same day he was fronting a dodgy property company for an associate of the Krays and, in no time, was living ''the life of morrie'' with an assortment of Chelsea-based upper-crust bad hats. An ingenious scam, involving the apparent theft of a Rubens or two, saw Cook undergo interrogation by the Dutch police force and gave him the impetus to forgo a life of actual crime in favour of a life of writing about it.

The Crust on its Uppers (1962) was an immediate succes de scandale on publication. Scandal however doesn't pay the rent for long, and with a second wife, Eugene, and first child, Sebastian, to support, the Sixties saw Cook combining novel-writing with stints as a Soho pornographer or running gambling parties. Much of the Sixties was also spent in Italy; catching the spirit of the age, the Tuscan village in which he settled decided to declare itself an independent anarchist state, and appointed Cook, naturally enough, its foreign minister; less probably, he also became minister of finance.

By the end of 1970, however, Cook had a (third) wife, Rose, a stepson, Nicholas, an infant daughter, Zoe, a large house in Holland Park, and books that still weren't selling. He worked as a taxi-driver, learning an inordinate amount about London low life but still not earning the requisite fortune. Something had to give and in the end almost everything did. The marriage broke up, the house went and he stopped writing books. He relocated to France, bought a derelict 15th-century fortified house in the south-west and began to work as a labourer. The family rejoined him for a while, and with them to feed writing fiction remained out of the question.

By 1979 the marriage had broken up for good and Cook was nearing 50, lean as whipcord, but looking at a life eked out as a day labourer and regular in the local bar tabac. In a panic he wrote a potboiler that was published only in France, returned to London for another couple of years, got married (to his fourth wife, Fiona) and divorced again, and worked as a minicab-driver on the night shift. Here he amassed the material that would emerge as perhaps the darkest, most completely noir of modern crime novels, He Died With His Eyes Open (1984).

In France, the book made Cook's name. It was filmed, with Charlotte Rampling in the lead role. Its successor, The Devil's Home On Leave (1985), was also filmed. Awards were won and Cook, in his trademark black jeans, black leather jacket and black beret, became a star act on the literary circuit, particularly following the 1990 publication of what many consider his best work: the tortured, redemptive tale of a serial killer, I Was Dora Suarez.

In Britain things were slower. Only when the novels came into paperback in the late Eighties did the Cook cult begin to gather momentum. A return to Britain in 1991, following the amicable breakup of his fifth marriage to Agnes, saw him belatedly receive the acclaim he had long deserved. The publication of his literary memoir The Hidden Files (1992) prompted an avalanche of interviews with this last Bohemian. Earlier this year he played a sell-out gig at the South Bank in the company of indie pop stars Gallon Drunk, with whom he recorded a remarkable musical interpretation of I Was Dora Suarez. Posthumous projects include a last novel, Not Till the Red Fog Rises, to be published in the autumn, a BBC drama series based on the crime novels and to be produced by Kenith Trodd, plus a third French film adaptation.

Robin Cook's last illness came not as surprise but as a sadness to all those who knew him. Derek Raymond the novelist will be remembered as a writer riven by a need to understand the darkness in human nature. But what those of us who knew him will remember is a man of boundless optimism, courage and humour, a man whose extraordinary enthusiasm for life could transform the mood of any room he entered.

LONDON NOIR; Obituary: Derek Raymond

Elizabeth Young / The Guardian

August 1, 1994

THE DEATH of Robin Cook (aka author Derek Raymond), confirmed bohemian and habitue of Soho drinking boites, will come as a shock to two generations of readers. The first encountered his early work in the sixties; the second are a much younger collection of literati and Cook cultists who, have come to revere the dark brutality of his eighties detective novels, known as "The Factory" series.

Cook was born in London to a wealthy, upper-class family whom he rejected completely. Although he always retained the strangulated vowels and exaggerated courtesy of his background, he walked out of Eton and immersed himself in crime, running a number of scams and fronting dodgy property companies for gangland figures. This world, with its dense Cockney slang, he immortalised in his first book "The Crust On Its Uppers" (1962, re-issued 1993).

Cook published five more novels and worked for two years as a London mini-cab driver before moving to France in 1974, where for a long time he did not write at all but laboured at menial jobs. In 1983, he made a triumphal return to literature with the wrenching semi-autobiographical He Died With His Eyes Open. This was the first in the celebrated Factory series which all feature an un-named, furiously compassionate detective who works for the department of "Unexplained Deaths", investigating the murders of humble, unimportant people. They are exceptionally powerful books - bleak and desolate - which present all the wreckage and agony of modern London. Cook had a unique ability to respond to the most eerie and sinister aspects of London. He could evoke the dark miles of closed doors in a Hanwell tower block as easily as the sudden scream that rips apart the sun-drenched, oddly menacing afternoon silence of Raynes Park.

In all, Cook will have published 12 novels in Britain (the last, Not Till The Red Fog Rises, will be out in November) two in France and his memoires, The Hidden Files. In the latter he discussed his own noir fiction and his fascination with the psychology of the psychopathic murderer.

In recent years, Cook moved back to London and became a familiar Soho figure, wearing his black beret and wreathed in blue cigarette smoke. He eschewed the glamorous, establishment-type literary success and aligned himself with disaffected younger artists in whom he saw echoes of himself. These included his agent Maxim Jakubowski, detective author Mark Timlin and the rock band, Gallon Drunk, with whom he recorded a CD of extracts from his most notorious novel I Was Dora Suarez (1990), the book that, to Cook's delight, caused a publisher to vomit over his desk.

Robin Cook died peacefully from cancer, lucid to the end. He was married five times. He is survived by two children.

Robin Cook (Derek Raymond), born June 12, 1931; died July 30, 1994

APPRECIATION: ROBIN COOK

Maxim Jakubowski / The Guardian

August 6, 1994

THERE was a wonderful contrast between the public persona of Robin Cook (obituary, August 1), whom readers will better remember as Derek Raymond, and the private man. The outside world saw the jovial, angular, gone-to-seed aristocrat, with his eternal black beret entertaining the Soho gallery in the Coach and Horses and the French Pub. For drinking acolytes, he was a figure of folklore; few knew that, after closing time, he would return to north London to wrestle with the writing demons on his cherished word processor and was a unique crime writer whose fictional world was brutal, realistic and harrowing in the extreme.

On the one hand, he could describe sordid murders, mutilations and perversions of the human soul in slow, minute, obsessive, almost loving detail, to the extent that many critics often found his novels gratuitous and exploitative. On the other, he was one of the kindest of men, gracious, polite - a genuine charmer for women, as his five marriages attest - available to friends, incapable of anger, a compassionate moralist always fascinated by the spectacle that human society kept in store for him. His sympathy was with the underdog, and the more gruesome the end for his characters, the more he conducted a bizarre but touching love affair with them.

In I Was Dora Suarez, beyond the paraphernalia of crime, serial killer, sexual excesses and investigating detective, what stays in my mind is one of the greatest love stories of our time between the nameless protagonist and the body and memory of Dora, the slain prostitute. In his own, utterly unromantic way, Robin knew that love was the only salvation, the only mercy life provides us.

Intensely private, his bragadoccio concealed a literary quest to understand evil, the reasons for lies, betrayals and killings. Despite all his years abroad, he was essentially a London writer, who sought life and characters in pubs, minicabs and shady drinking clubs. He will now take his place in a limited pantheon of authors who could evoke the dark side of our capital, the truth behind its screen of quiet mews, green parks and urban sadness.

His final novel, Not Till The Red Fog Rises, to be published this autumn, is a claustrophic race against time through the streets of London, seen through the eyes of a die-hard villain, for whom, despite his genuine savagery, Robin Cook manages to engineer our empathy, all the way to a literally apocalyptic ending. It will be a fitting tribute to a writer who transcended the crime genre, and who spoke as few 60-year-olds could to younger generations, as the queues of teenagers at his readings and signings attested.

Despite his bleak vision, Robin Cook loved the world and the world loved him back. He was becoming the object of a cult, and ironically, his death and future film and television adaptations, will accelerate the process. It would have made him smile, thinking of all the years when the rewards were spare and he lived on the breadline.

I will sorely miss that rakish black beret and that crooked smile of rotten teeth, as will all his friends in London and Paris, lovers of crime fiction and a myriad of anonymous drinking partners.

CRIME RATION: SOHO SLEAZE SUPREMO

Jane Mccloughlin / The Observer

January 8, 1995

Not Till the Red Fog Rises is one of those rare crime novels which remind us that Crime and Punishment and The Secret Agent are genre thrillers. But you read it at your peril, because the late Derek Raymond's Soho drinking clubs, sleazy alleys, damp bedsitters and artistically violent low-life characters become more real than your own fireside armchair, and leave a disturbing aftertaste.

This is a terrific book, with a strong basic story, involving hi-jacked blank passports and missing Soviet nuclear material which, incidentally, proves that reports of the death of the thriller, post- Cold War, are much exaggerated. On the contrary, Raymond shows that the break-up (or -down) of the Soviet Union opens great new vistas of plot-productive ground as capitalism and corruption are left floundering in the aftermath.

The broad political dimensions, though, are not the point. It is the small, bleak community which compels. Raymond's characters seem to come out of Dante's Inferno. Like the protagonist, Gust " on parole after serving 10 years for armed robbery " they are unable to resist the awful inevitability of who and what they are. At the point of social and personal disintegration, they kill, or are killed, as part of a world in which violence is both currency and communication. The violence is stomach-churning, but not cheap or sensational. Its function is quasi-spiritual, an unsentimental parallel to Graham Greene's use of Catholicism.

Because of this violence, and the macho atmosphere of a criminal world where females are either whores or mothers, women may not think well of Derek Raymond " the nom de plume of Robin Cook, who died last summer on the point of becoming a cult figure here and in France. Women, however, are the agents of catharsis in his anarchic world, even when the men try to stamp them out.

This is a bleak book, but also funny and defiant. The quality of the writing stands comparison with Graham Greene, Eric Ambler, even Conrad. As to enjoying it, that's another matter " Derek Raymond goes well beyond entertainment into the more ambivalent realms of perverse compulsion.

LUCIFERIAN FANTASIES

Virginia Osborne / The Sydney Morning Herald

May 20, 1972

On the back of book jackets it is often the custom to put excerpts from reviews of the author's previous books. In one of these, I was enchanted to read a particular reviewer's confident statement: "This is a book." There speaks a man, I thought to myself, who is not afraid to sit squarely and economically on the fence.

And paradoxically (unless, of course, he was talking about a rabbit hutch or a jigsaw puzzle) a man who was still determined to tell the truth.

Fence-squatting apart, I had no idea why there was no adjective qualifying his statement, but with The Tenants of Dirt Street by Robin Cook, I thought for a while I was beginning to see the light. The poor reviewer just didn't know what to think. And neither did I.

The book to me was distinctly unfunny. It was overworked or underworked. However, its style was good so perhaps the problem lay only in my sense of humour not being similar to the author's. A rather cruel reason to dismiss his book. I decided to give a precis while I considered the problem further.

Lord Eylau is an impoverished peer of 39 given to drinking bouts. On one of these he is taken in by a vicar and falls helplessly in love or lust with his blind wife, Helen. She is perfectly willing to be wooed and removed from the vicar as long as Lord Eylau can give her one thousand pounds in cash. In trying to do this he falls into the hands of the chairman of Amalgamated Vice, Mr Viper, who offers to lend Eylau the money in return for his services running a Fantasy House as Louis XVI with Helen as Marie Antoinette.

Problems start when Helen takes to the Fantasy House like the proverbial duck. She is pursued by all the clients and denies her favours to none. Eylau becomes rapidly unimpressed and throws a tantrum which is meant to destroy his job but instead consolidates it. He and Helen split up and she goes off with one of the clients, finally to end up with Viper himself.

Writing it down I became more and more convinced that the book was not a success. But I also realised that the fault lies not so much in the humour-- or lack of it-- as in the characters never acting of their own logical volition but because the author demands it. And it is this which is gives the book its curious static quality -- running on the same spot while giving the impression of speed. It's not that the author can't write. He can, but he has forgotten to put the concrete between the bricks of the plot, and with the first puff of criticism it all falls down.

Back to top